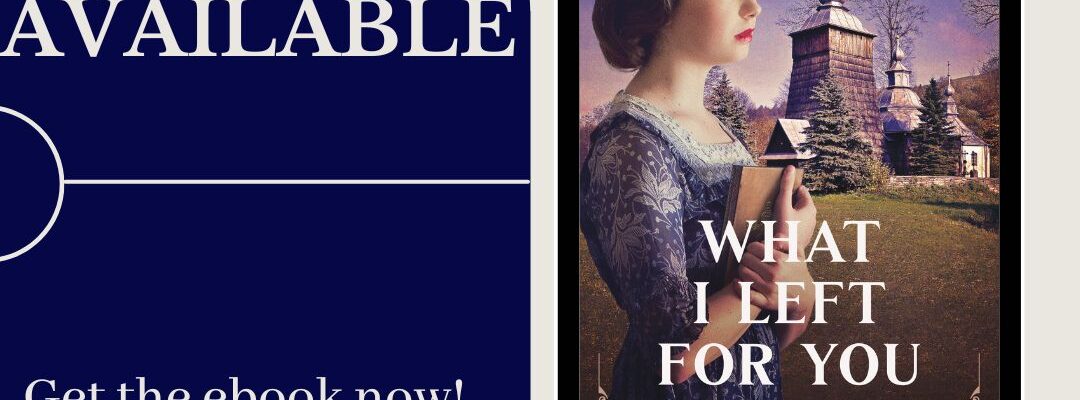

It feels like it’s been a long time coming for What I Left for You, but the day is finally here. The ebook is now available! The print version is coming December 1st.

In honor of the release of the novel, which focuses on the plight of a Polish ethnic minority during WWII, I’m starting a series about the Lemko people and my journey to discover my family roots.

You can get your copy of What I Left for You here.

I stared at my computer screen in front of me. For years, I had been searching for my great-grandmother, Anna. I got no good information. Census records in the US weren’t helpful. Some listed her birthplace as Czechoslovakia, while others had it as Austria. I had heard before that she might have been born in Czechoslovakia before, but never Austria. There were no records that I had come across that listed the city or town where she was born.

Until that one day. While searching for my great-grandmother, I ran across a passport application recorded in Warsaw, Poland, for an Anna with the same last name, though spelled differently. Her birthday was listed as 1903, which matched the birth year I knew for my great-grandmother’s niece. As I read through the application, my heart was pounding. This Anna was born in the United States but went to Poland with her family in 1906. It was now 1923, and she wanted to return to the US, and she would be living with…

I started to cry when I saw who her sponsor was. My great-grandfather. The name and address were correct. There could be no doubt about it. It had taken me years, but I finally made the jump to Europe and discovered that my great-grandmother was not born in Czechoslovakia but in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is now Poland.

Of course, good little researcher that I am, I had to find out all I could about Dubne, the town they were from. That’s when I first came across the term Lemko. What on earth was that?

Lemkos are a Slavic people that settled in the Carpathian Mountains of Southern Poland, Northern Slovakia, and Western Ukraine. The mountains kept the world at bay, and they developed their own language, customs, and form of Christianity. For the most part, they were very poor, many of them eking out a living from the rocky ground.

This is a “black house.” It was called that because the poorest people couldn’t afford to have a chimney built. The smoke from the cooking and heating fires stayed inside the house and covered the walls with black tar. If you look at the cemetery records from Dubne, you would be old if you lived into your fifties. Conditions were brutal.

This is where the family animal was kept. The most they could afford was one sheep or one pig. Since this was their most prized possession, they couldn’t take the chance of a wild animal or a neighbor taking away the sheep or pig, so it lived in the house with them.

With all of them. Up to eleven people would live in a two-room house. When I mentioned that in What I Left for You, my editor questioned if I had made a mistake. No,I didn’t. I have no idea how they fit all those people in there, but they did. As I was tracking one branch of our family tree, I kept coming up with people living in house 43. Over and over and over. They stuffed that house full. Grandparents, parents, and children all lived together.

Lemkos are also known as Lemko Rusyns, Rusyns (especially those born in Slovakia, like my great-grandfather), and Carptho-Rusyns. I discovered that my great-grandfather was born in Čurč (sounds like church), Slovakia, and I wondered how they ever got to know each other if they were born in different countries. Turns out that they married in New Jersey, but it is possible they were acquainted before they emigrated because Čurč and Dubne are only seven kilometers from each other. Both villages lie close to the Polish/Slovak border. I do believe they did know each other before coming to the US because my great-grandfather’s sister married a man from Dubne a week after my great-grandparents got married.

This is what the Slovakian countryside looks like.

Over the coming days and weeks, I’ll share more with you about the Lemko people, but I’m proud to be Lemko Rusyn. I’m descended from a long line of strong and determined women, and I wrote my heroine in What I Left for You to reflect that.