In reviews of A Picture of Hope, there has been at least one comment that the even that sent Nellie to France, when she stowed away on the hospital ship The Prague, was just too unbelievable. That comment caused me to chuckle because it is one of the most historically accurate parts of the book.

As A Picture of Hope took shape, I needed a way to get Nellie into France. I read that female journalists weren’t allowed into the country until several days after D-day. More than anything, I wanted her to be there sooner so she could be in the heart of the action. It’s what Nellie herself would have wanted. It’s what fit best with her character.

So I went in search of a way to get Nellie into France as soon after D-day as possible. For several years, I’ve been researching the role of female journalists during the war, so I turned to one of the books I have and rediscovered the story of Martha Gellhorn.

She was born in St. Louis in 1908 to parents who championed humanitarian causes. She dropped out of college to pursue her dream of being a journalist and worked for such publications as The New Republic, Vogue, and Women’s Home Companion, as well as United Press. She also worked for the Federal Emergency Relief Agency, traveling around the country and chronicling how the Depression affected people. She made lifelong friends of the Roosevelts.

In the late 1930s, she met Ernest Hemingway. The two became involved and traveled Europe together, chronicling the brewing storm. They married in 1940, though by D-day, their marriage was all but over, especially when he was given credentials to go to Europe and she was not. She managed to get to England on a munitions barge.

In late May 1944, all the reporters in England knew the Allied invasion of France was imminent. However, American military brass would only allow men to be embedded with the troops. The women wrote a letter to the higher-ups that eventually got them into France, but not until several days after D-day.

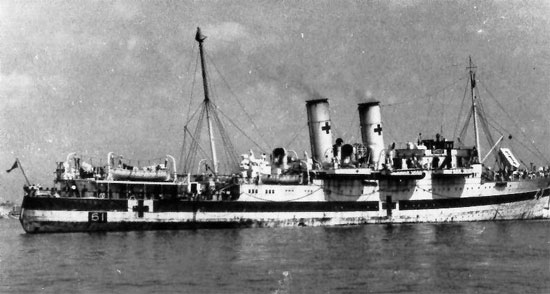

This wasn’t good enough for Martha, especially with Ernest on a boat bobbing off the Normandy coast. She found her way to Southhampton and slunk along the dock. When some military personnel approached her, she flashed an expired press badge, boarded the hospital The Prague, and was soon on her way to France. While Ernest sat in his ship, she worked all day alongside those on the boat, bringing the wounded on board, providing them water and food, giving help where she could be of help. Come night, she waded onshore as a stretcher bearer and got a first-hand scene of the carnage.

She had the scoop. The best part for her was that she had gotten her story ahead of Ernest.

She continued working as a journalist covering other wars and writing a number of books. Along the way, she had a string of failed relationships and marriages. Suffering from blindness and ovarian cancer, she died by suicide in 1998 after swallowing a cyanide pill.

What drew me about Martha was her tenacity and her unwillingness to be bested by anyone. She was going to accomplish her goals one way or another. It is this tenacity and drive that I shared with Nellie and why I chose to use the TRUE story of Martha Gellhorn to inspire part of A Picture of Hope.

Read part one of this series here. It’s about the tragedy at Oradour-sur-Glane and how I chose the picture of hope.

Purchase your copy of A Picture of Hope to see how I fit this story into the novel.

Sources:

Reporting WWII: Part Two: American Journalism 1944-1946, published by The Library of America, copyright 1995

The Extraordinary Life of Martha Gellhorn, the Woman Ernest Hemingway Tried to Erase Ernest Hemingway, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/tradition/a22109842/martha-gellhorn-career-ernest-hemingway/

This is so interesting to watch you weave true and fiction together to make such page turning books. I wish the younger generation appreciated what has gone before so they can have the life they do.